Albert Bierstadt, a German-born artist, is widely considered to be among the best landscape painters ever. Naturalistic with a hint of romanticism, Bierstadt’s panoramic landscape scenes were inspired by the terrain of the unsettling American West. Intense travel around North America, Europe, and the Bahamas offered Bierstadt a firsthand perspective that informed his depictions of landscapes.

To duplicate his massive paintings, Bierstadt was proficient in photography and prepared sketches and stenography. Although Bierstadt’s contributions were under-appreciated during his lifetime, they are today considered a significant element of American heritage.

click here – The Most Insane Thing You’ll Ever See: Zorb Balls

Early Life and Education

After leaving Germany in 1831, Albert and his family settled in Massachusetts. He was always interested in painting. Initially, he advertised his services in New Bedford as a talented monochrome painting instructor. Then, between 1853 and 1857, he learned at a famous painting school while tutored by Achenbach Andreas and Carl Lessing Friedrich.

Albert began his career as a painter in New England and New York, but he frequently traveled to get a firsthand look at the landscapes he would later portray. A federal land surveyor named Colonel Frederick W. Lander took Bierstadt on a trip out West in 1959. He brought back a wealth of sketches from his travels that became paintings.

It was in 1864 that he made his first panoramic landscape, but in 1863 he went back to the wild West with author Fitz Hugh Ludlow. With his painting of the Rocky Mountains’ Lander’s Peak, Bierstadt launched his short-lived but highly successful career as a renowned landscape artist.

Painting Characteristics

Albert Bierstadt was a member of the loosely affiliated Hudson River School of painters who shared aesthetic values like attention to detail and a penchant for creating a moody, ethereal atmosphere through light. Along with Thomas Moran, Thomas Hill, and William Keith, he was a part of the Rocky Mountain School, which portrayed the western terrain. In 1860, he was invited to join the National Academy of Design, an honorary group of New York City artists dedicated to advancing the visual arts. Albert Bierstadt style of painting also won him honors in Bavaria, Austria, Belgium, and Germany.

There were two distinct phases to Bierstadt’s rise to fame. First, he could better develop and perfect his naturalistic painting technique through his studies at the Dusseldorf School and subsequent travels to many attractive locations. Second, Bierstadt’s works were well-liked by advocates of American Transcendentalism, who shared the Hudson River School’s idea that art might affect social and spiritual transformation.

The Portico of Octavia Rome, by Bierstadt, was the first of his paintings purchased by the Boston Athenaeum in 1857. In other words, he was beginning a career as an artist. His first major public showing was at New York’s National Academy of Design in 1858. In 1867, Albert was given to Queen Victoria by Napoleon III and granted the Legion of Honor for his services to the arts and the presentation of the United States Capital. Throughout his career, he produced at least 500 paintings and probably as many as 4,000.

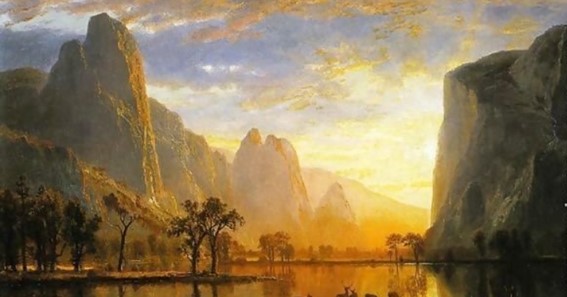

All of these can be found in museums around the United States and Europe. Indians in Council, The Sierras Sunrise, and the Yosemite Gates are just a few of his breathtaking landscapes at the Smithsonian Institution today.

Valley of the Yosemite 1864 – Albert Bierstadt

click here – Autumn Roof Maintenance Checklist and Tips

Characters of Painting

Some of Albert Bierstadt’s canvases measured over ten feet in width, which was highly unusual. His wide-angle, intricate vistas perfectly conveyed the grandeur of this mysterious and unsettling region. He used bold hues and contrasting values to evoke an emotional response in his viewers. His use of contrasts not only lent his paintings a feeling of depth and drama but also helped set the tone. His landscapes, which were natural and life-like, were realistic yet romantic thanks to their expansiveness and depth, as well as their vivid texture, keenness, and comprehensive textural nuances.

Throughout his career, Bierstadt was the target of severe criticism from his contemporaries. His use of massive canvases, which dwarfed those of his contemporaries, earned him an arrogant reputation. His fellow artists questioned its romantic use of light and color. In some of his works, Bierstadt deviated from realism in favor of depicting scenes as he imagined them. The others questioned his integrity because he used ultramarine water or verdant greenery.

Similarly, some artists have complained that including atmospheric features like fog, clouds, or mist only romanticizes the otherwise colorless and lifeless landscape. Albert Bierstadt occasionally alters a landscape’s specifics to get his desired effect on the observer.

The Final Years

By the turn of the century, Albert Bierstadt had established himself as the preeminent American landscape painter. Malkasten, his home and studio on the Hudson River, is where he spent the prime of his life and work in 1882. Then, in 1886, he tied the knot and began a life filled with travel.

A fire at his studio destroyed many of his paintings and his collection of engravings and presents from Army officials like General Sheridan and General Custer from his time spent in the West.

Shortly after, Albert’s wife died. He remarried, but the popularity of French Impressionism meant that his works were forgotten. At 72, Bierstadt died as a bankrupt and mostly forgotten artist in New York City. He had gone the previous year and filed for bankruptcy. Endless valleys, towering mountains, and crashing waterfalls are just a few ways in which Albert Bierstadt transformed the sometimes harsh, lifeless, and barren nature into stunning landscapes.

Surveyor’s Wagon in the Rockies – Albert Bierstadt

The Legacy of Albert Bierstadt

Bierstadt and other second-generation Hudson River school artists rose to fame in the nineteenth century for their sweeping panoramas of the American countryside. But Bierstadt’s emphasis on the uncharted American West distinguished him from other Hudson School colleagues. In this way, he played a part in introducing the vast majority of Americans to the country’s wild borders and wilderness. Indeed, his depictions of the United States as a “Promised Land” influenced American culture and motivated a new wave of explorers and settlers to move West.